Article | Life with a Capital L

Article by Alice Courtright, published in Fjord Review magazine

During a bombing of Berlin in World War II, the young dancer Ludmilla Chiriaeff (née Otzoup Gorny) waited in a makeshift bomb shelter with her father. Alexander Otzoup was a writer and poet with a powerful imagination, who gathered regularly with other Russian émigrés to share work and talk.

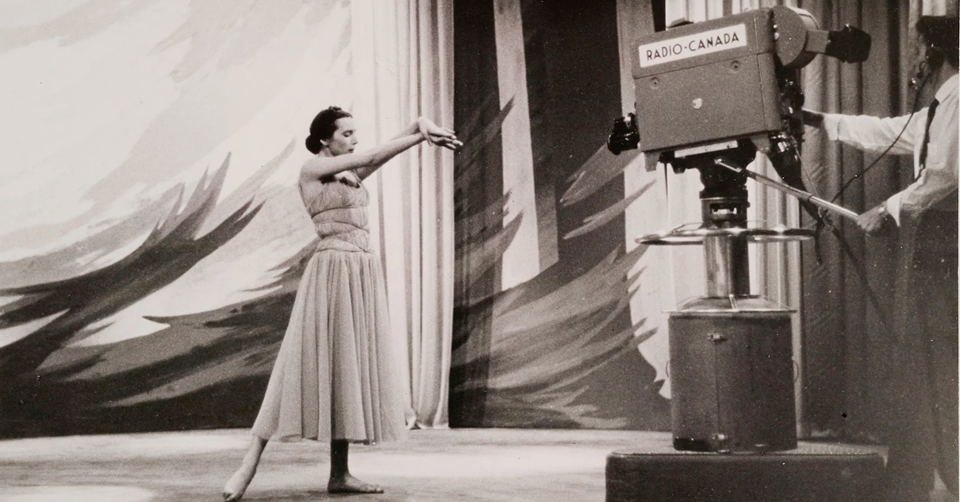

Ludmilla Chiriaeff. Photograph by Henri Paul

He comforted his daughter, and his consolation shaped her understanding and, later, the trajectory of her life. Coming out into the daylight after the bombing, Chiriaeff later recalled in an interview, they saw : a house dripping with phosphorus, where the edges of the window were burning around the flames. And my father said, “Look! I’m not crazy, look, this house is like Mozart.” And the next house, where flames were coming right from the basement, he said, “That, that is Wagner.” He gave me a way to overcome the horrors of war. And so, survival became a strength I chose to overcome the destruction I witnessed around me. I really had the feeling, the very deep feeling, that I survived for a reason, and that I had a mission, a duty to do something, that I was really in search of my life. Where is my place?

Ludmilla Chiriaeff

A few months later, Chiriaeff, who was a soloist with the Berlin Opera, came upon the ruins of her old house. She was struck by the flower of a little plant growing out of the rubble. It was a potato that had germinated in the cellar. Like her father, she read the scene symbolically, as a testament to resilience: “I understood that this is life. Life with a capital V. That Life never stops, that we must continue, that we must seek, that we must fight and never stop. Because Life is about moving forward, it’s never going backwards, it’s never even standing still.”

When the war arrived in full force in Berlin, Chiriaeff, whose family practiced the Russian Orthodox faith, was sent to a labor camp north of Berlin, because her father was of Jewish heritage. Chiriaeff was measured and certified as one quarter Jewish. She was forced to work with metal and lead for Nazi armaments. Though she was hardly fed and there was no protection from the bombings, her father’s sense of meaning-making and vision gave her courage. “When I was in the camp,” she has said, “I never felt horror, because he set in my mind… there are two ways of being in life. Either you are crushed forever, or you have a different antenna, a different dimension.”

During a bombing raid, Chiriaeff escaped the labor camp and fled to Switzerland, where she again pursued her career in dance, founding her first ballet company. She married the painter Alexis Chiriaeff and had her first two children. Soon thereafter, they sought asylum in Canada, where she would make a profound impact on arts and culture in Québec. She founded the internationally acclaimed company Les Grands Ballets Canadiens and the successful ballet school L’École supérieure de ballet du Québec, both in Montreal. By her death, in 1996, she had received numerous national and Québecois awards, honorary degrees, Poland’s Nijinsky Medal, and other international recognitions. She was regaled for her irrepressible vision of life, which she passed down to innumerable dancers, colleagues, and young artists. On the occasion of International Women’s Day, in 2022, Chiriaeff was designated a “Historical Figure” by Québec’s Minister of Culture and Communications. This year marks Ludmilla Chiriaeff’s centenary, which Montreal is commemorating with a series of events, including the Prix Ludmilla, panel discussions, and performances by Les Grands Ballet Canadiens and L’École supérieure de ballet du Québec.

In late May, the sold-out opening night of the school’s performance was attended by Mathieu Lacombe, Quebec’s Minister of Culture; Gilles Vigneault, legendary poet and singer; choreographers, dancers, composers, family, devoted former students, and many others who had been touched by Chiriaeff.

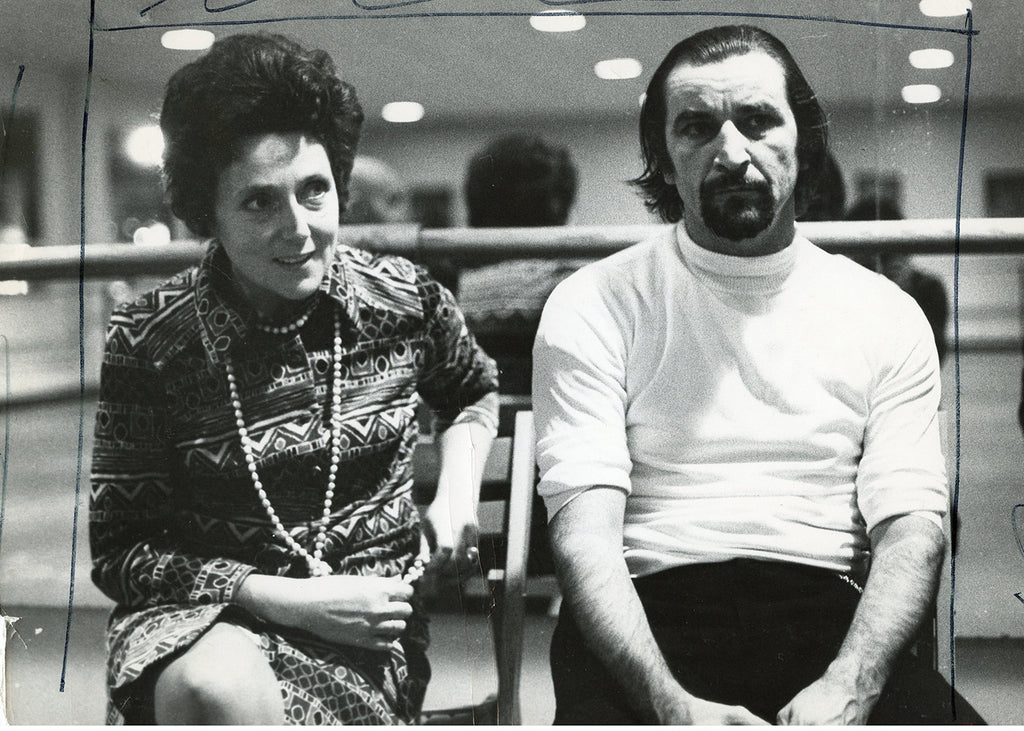

Ludmilla Chiriaeff and Maurice Béjart

Generations of Montreal dancers are celebrating Chiriaeff’s centenary this year because a major part of her mission was education. “She was passionate about not only creating but ensuring a solid future for the art of dance in Québec,” Katia Mead, her youngest daughter, told me in a recent interview. Chiriaeff created the first professional institution in Québec dedicated entirely to the training of dancers, teachers, and choreographers. “She believed dance needed to be accessible to everyone and traveled across the entire province to develop new talent and establish local feeder schools for L’École supérieure. Whenever she discovered gifted students who needed support, she raised funds to provide grants for free classes and housing. She was ‘Madame’ but also a mother figure to all.” Graduates of L’École supérieure have gone on to perform at companies nationally and internationally, including Ballett Zürich and Opéra de Paris.

The renowned Canadian choreographer and longtime director of the Alberta Ballet, Jean Grand-Maître, is one of those graduates. He credits her with his turn toward choreography. “She opened a little door in my mind,” Grand-Maître said at L’École supérieure’s performance in May. “I wasn’t sure what to do in my last year at her school [in the 1980s]—I hadn’t reached the caliber I’d hoped for as a dancer. I was a bit depressed, and Madame sought me out. She said that everything she taught me was not only in my legs but in my head, and she said that with that, I could move mountains.” Chiriaeff commissioned his first piece. “She had a knack for spotting vocations, for whether a dancer should become a doctor or an actress or even a choreographer.” Grand-Maître went on to a prolific career and only recently retired, after twenty years at the Alberta Ballet. He has now created a piece for school and company, which will premiere in October, based on Chiriaeff’s life as a refugee. “Madame taught not only dance,” Grand-Maître said, “but the history of dance. She showed you what a huge responsibility it was to be an artist: to inspire truth and beauty, to provoke and challenge, and to connect communities through an encounter with aesthetics.”

Throughout her life, Chiriaeff regularly credited the influence that the Russian choreographer Michel Fokine had on her. Fokine, who is best known for his work for the Ballet Russes, spent time in Berlin at the Chiriaeffs’ home. One day, the young Ludmilla and he had a remarkable exchange. Questions swirled, like, “How do we sense movement without music, just a score?” Fokine made a creative roadmap for her. He sketched a dancer at the bottom of a page and drew four characters above her. He said, Chiriaeff recalled, “To be a dancer and creator, you must be as musical as a composer, as sensitive as a poet, as strong and supple as an athlete, as self-critical and severe to yourself as a very severe critic would be, but also open to the many many possibilities of mixing colors like on the painter’s palette. And then, maybe, you will serve the dance.”

Perhaps it was this conversation, in which service to dance was the highest goal, that led Chiriaeff to make bold statements like, “Ballet is the most spiritual of all the arts.” For Chiriaeff, ballet was a vehicle by which she could serve the people who had welcomed her and her family from a time of war and hardship.

Students of the École supérieure de ballet du Québec perform in a tribute to Ludmilla Chiriaeff

Almost thirty years after her death, the school and company are still thriving, and the spirit of service and dedication to the wider culture have permeated the commemorations in Chiriaeff’s honor. Adrian Batt, a local contemporary choreographer and graduate of the school, reflected on Chiriaeff’s impact. “I believe that in the institutions she created and the dance community in Montreal that she helped engineer, she has left a legacy and lesson of service for future generations of Montreal artists. I think of this constantly, as someone who had the opportunity to receive a dance education in a place that she built. Her greatest quality of perseverance and her ability to share dance has created a gift for everyone who comes into contact with the school. The key is asking yourself how you can pass it on.”

Anik Bissonnette, current artistic director of L’École supérieure de ballet du Québec, said at its annual show that it was a “pleasure to work inside Madame’s vision” of adaptability to every generation, poeticism, and reverence for the traditions of classical ballet. Bissonnette danced as a principal with Les Grands, and performed for Chiriaeff at the Prix du Gouverneur in Montreal in 1993. Her elegant, evocative performance brought Chiriaeff to tears. It was especially meaningful, as Chiriaeff was at the end of her life, suffering from a terrible lung disease that stemmed from the time when she’d been forced to work with lead, in the labor camp.

Students of the École supérieure de ballet du Québec perform in a tribute to Ludmilla Chiriaeff

This annual show for L’École supérieure, which Bissonnette designed, reflected the breadth of Chiriaeff’s passions in dance. A mystical piece by Fernand Nault entitled “O Fortuna” led the program. Set to a portion of “Carmina Burana,” it invoked the role of Fortune in defining destiny. Next was a charming work by character dance expert, choreographer, and long-time faculty member Monik Vincent, titled after the song “Moi, Mes Souliers” by the beloved Québécois singer-songwriter Félix Leclerc. The audience sang along and clapped; there was tremendous joy in the theater as the children danced. The lyrics magically seemed to realize the story of Ludmilla herself.

Me, my good old shoes traveled a lot

They carried me from the school to the war

With my hobnailed shoes I crossed

The world and its misery.

Me, my good old shoes crossed through the fields

Me, my good old shoes trampled the moon

Then my good old shoes slept with fairies

And had more than one of them dance.

Moi, mes souliers ont beaucoup voyagé

Ils m'ont porté de l'école à la guerre

J'ai traversé sur mes souliers ferrés

Le monde et sa misère.

Moi, mes souliers ont passé dans les prés

Moi, mes souliers ont piétiné la lune

Puis mes souliers ont couché chez les fées

Et fait danser plus d'une.

The rest of the program consisted of a delightful excerpt from “Swan Lake” a short work by Chiriaeff herself; a portion of Grand-Maître’s aforementioned “Continuum; Les Héritières,” by the contemporary Canadian choreographer Anne Plamondon, and a moving concluding piece by Sophie-Estel Fernandez, “Il me reste un pays,” based on poetry by Chiriaeff’s friend and collaborator Gilles Vigneault. Between each piece, there was an interlude with a character dancer playing Chiriaeff, accompanied by her recorded voice from the Radio Canada archives. She spoke of her pivotal moments in the war, of her family, of her love of the French-Canadian spirit and countryside.

The pride of the French-Canadian audience was palpable throughout the program, and cries of “Brava!” rang out again and again—throughout the performance and at its end, when everyone rose to their feet.

Les Grands Ballets Canadiens will present “Ludmilla” a tribute to the boldness and visionary spirit of Ludmilla Chiriaeff, at La Salle Wilfrid-Pelletier, Place des Arts, in Montreal from October 24 to 26, 2024.